There are a lot of approaches to budgeting and personal financial management, it seems. Some are rather complicated, while others make you wonder whether their advocates actually practice what they preach (*cough* *cough* Dave Ramsey *cough*).

I use GnuCash for managing my personal finances. It is a completely free, open source application available for the three major desktop platforms — Windows, Mac OS X and Linux. As of the time I write this, it is not available on any mobile platforms, though you can run it on a Windows-enabled tablet such as the Microsoft Surface (in my case, the Toshiba WT8-B).

To use the system I describe herein, you need to be familiar with GnuCash and double-entry accounting, which is well beyond the scope of this article, and I will assume that if you keep reading beyond this point that you are familiar with both concepts.

Some of the concepts described herein can likely be applied to other personal accounting systems, such as envelope budgeting and paycheck budgeting.

“Envelope budgeting” with GnuCash

“Envelope budgeting” is simple: divide your income into separate envelopes and spend from those envelopes. Dave Ramsey advocates using physical envelopes with physical cash. And many other advocates of “envelope budgeting” say the same. But “cash only” tends to mean different things. For example, a “cash only” clinic is one that does not accept insurance of any kind. And my spending is “cash only” in the sense that I rarely use credit cards anymore.

You implement “envelope budgeting” with GnuCash by using its concept of “sub-accounts” — do a Google search for “GnuCash envelope budgeting” (without quotes) to find articles on it. When you receive your paycheck, you would split the income into the various sub-accounts. Divide the income by splitting the transaction1See section 4.2.2 of the GnuCash manual, or by moving the money through separate transactions. I prefer the latter as it makes later adjustments a lot easier.

If you practice zero-sum budgeting (often erroneously called “zero-based budgeting” by many, including Dave Ramsey), your entire paycheck is split off into sub-accounts. Expenses fitting those budget categories would come out of the sub-accounts, and you’d use transfer transactions to move cash between those envelopes as needed.

You can still reconcile transactions against your bank account doing this — check “Include sub-accounts” when reconciling.

Most envelope budgeting systems go on an ever-running basis or on a monthly period. I prefer paycheck budgeting combined with envelope budgeting. And I believe, based on my own practice, that is the optimal budgeting and financial management setup.

Paycheck budgeting

Most budgeting systems use a one-month cycle. Indeed every budget system or application I’ve seen locks you to a one-month cycle. For paycheck budgeting, your budget period is the pay period instead of a set calendar month. It is a lot easier to manage your money when budgeting only on the pay period.

Organizing expenses is easier when your pay cycle is semi-monthly or monthly. Your employer pays you on the same days of the month (or thereabout) and your bills are due on the same days of the month. Ongoing organization is necessary if you are paid weekly or bi-weekly, as your paydays are always changing.

Regardless paycheck budgeting forces you to organize your expenses. Create a spreadsheet showing your monthly bills, including the due day and amount owed. Include in that the day your credit card accounts issue a statement. This will be necessary to create future budgets.

Create budgets for several months at a time — at least one fiscal quarter if not an entire fiscal half. This allows you to balance expenses across pay periods. You’ll want to account for expenses such as pre-orders, property tax payments, and other anticipated expenses. If you are paid weekly or bi-weekly, this helps avoid having pay periods with a lot of money available and others with little available.

Paycheck “envelope” budgeting

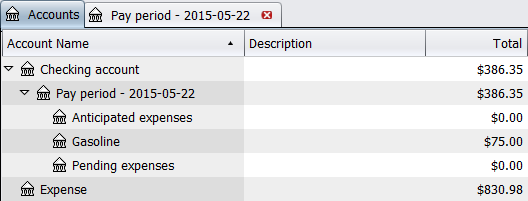

To combine paycheck budgeting with envelope budgeting, you’re basically creating an envelope for each pay period, then envelopes inside that envelope for budgeting categories:

- Checking account

- Pay period – 2015-05-22

- Bills

- Gasoline

- Loan payments

- Lunch

- Pay period – 2015-05-22

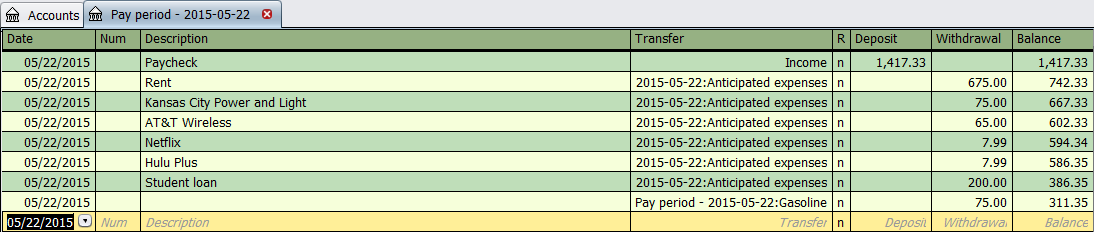

Let’s start with an example. Let’s say that you, the reader, are a single person living in Kansas City, Missouri, making $50,000 annually and paid bi-weekly with no additional deductions beyond the requisite taxes — gross pay would be 1923.08, and net pay after deductions is 1417.33.

Based on the spreadsheet you made earlier, let’s say the expenses that overlap with this paycheck are

- Rent: 675.00

- Power bill: 75.00

- Wireless: 65.00

- Netflix: 7.99

- Hulu Plus: 7.99

- Student loan: 200.00

New paycheck

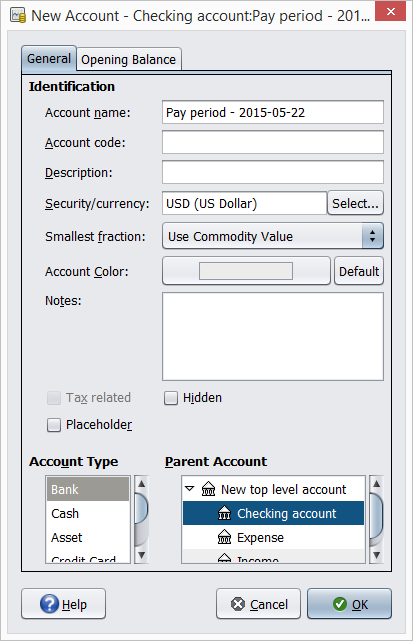

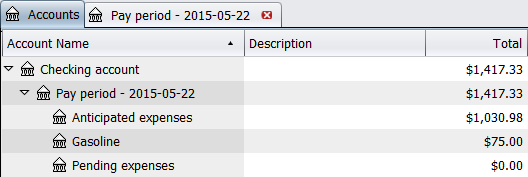

When a new payday arrives and the paycheck is direct deposited into my checking account, I’ll set up a new budget account as a child to the bank account:

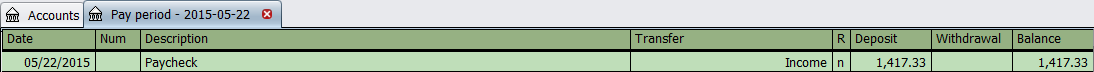

and add the initial deposit. I typically track taxes and other paycheck deductions in separate expense accounts — in part due to the 401(k) I have through my work — but for simplicity, I’ll only do the net income for this deposit.

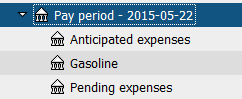

From here I’ll start making allocations. You should’ve noticed from above that the pay period account has two additional child accounts: “Anticipated expenses” and “Pending expenses”. Allow me to explain these categories.

Anticipated and pending expenses

Most who use a financial management system are familiar with cleared and un-cleared expenses. I’ll be discussing three kinds of expenses: anticipated, pending and confirmed. These are not expense types that GnuCash enforces in any way, but categories I imposed on myself.

- Anticipated expenses are expenses you anticipate will be charged to your bank account during the pay period. These could be obligations that fall within the pay period, pre-orders that may deliver during that time, and anything else you can reasonably “anticipate”.

- Pending expenses are expenses you have already initiated with the recipient — checks in the mail, EFTs waiting to be acknowledged by the bank, and so on — but haven’t yet been deducted from your bank account balance. I classify expenses that will be automatically charged to my bank account as pending expenses as opposed to anticipated because I don’t have to do anything to initiate payment.

- Confirmed expenses are expenses that the bank has deducted from your account balance, whether they have “cleared” or not. These are the only expenses that target an Expense account.

The progression of expenses goes anticipated to pending to confirmed. Debit card payments will likely hit your bank account immediately and deduct from the available balance, so while those payments are initially anticipated, they will target the appropriate expense account when started with the recipient.

By keeping track of expenses in these three categories, you can keep the balance that GnuCash displays for the “Checking account” account in synchronization with the balance reported by your bank while also keeping track of what you have spent. Transactions that target the Anticipated or Pending expenses envelope accounts don’t deduct from the total balance for the checking account. That balance is only affected when the expense targets a separate expense account. But they do deduct from the balance of the pay period envelope, which is what matters.

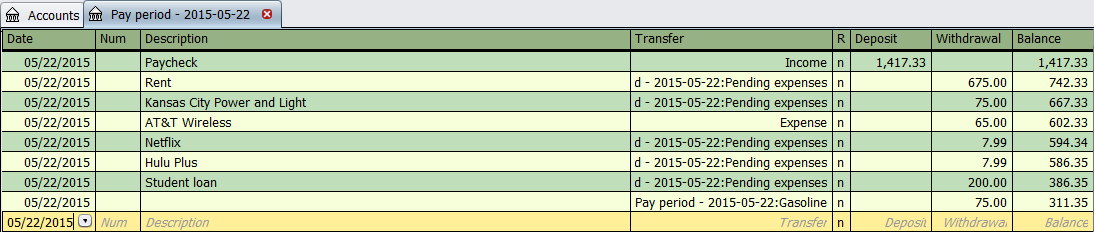

Let’s illustrate by setting up the anticipated expenses for this paycheck.

The current balance of this envelope account, 311.35, I refer to simply as “discretionary” — money not allocated toward anything else, so I can allocate it elsewhere if I want, or I can spend it freely. In zero-sum budgeting you would set up additional child accounts similar to the Gasoline account to allocate funds toward those other spending categories such that either no money would be going into the main pay period envelope, or the remaining “discretionary” would be allocated to spending categories instead of left like this.

In general you’d want to allocate funds for expenses you can reasonably anticipate. Gasoline is a good example. I have two SUVs — an Equinox and a Santa Fe. The Santa Fe tends to get filled up only once per pay period, while the Equinox gets filled up twice, and I can approximate how much I’d need to allocate for gasoline based on that.

Let’s look at the account page after this.

As you can tell, the Total for the “Checking account” is still the same as the initial deposit. That is simply because it is showing the sum total of all sub-accounts underneath it along with whatever balance might exist in that account — currently for this example, it’s zero.

Initially all of these transactions are listed as “anticipated”. Neflix and Hulu auto-bill, so I’ll change those to “pending” pretty much right away — I might even list them as “pending” instead of anticipated when making the initial entries. Then I’ll pay the remaining bills. The power bill, student loan, and rent are paid by EFT — electronic funds transfer — so those transactions get changed to target the “Pending expenses” account so I know those are payments that have been made but that haven’t yet been initiated with the bank, transactions for which I don’t need to do anything more. If I’d written a check for any of these payments, they would have targeted “Pending expenses” as soon as the check was dropped in the mail.

The wireless bill I pay through my debit card, so it targets the appropriate expense account immediately.

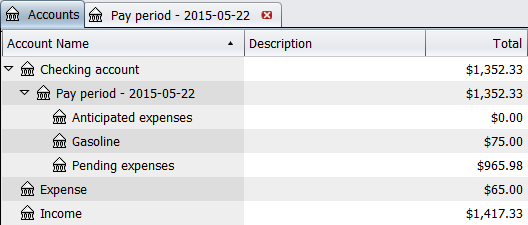

And looking at the Accounts page, we can see that the balance of the checking account has gone down slightly, because of the AT&T Wireless expense. If this were a real checking account with online access, the online balance would reflect that AT&T Wireless has already been acknowledged by the bank while everything else won’t be till the next business day at the earliest.

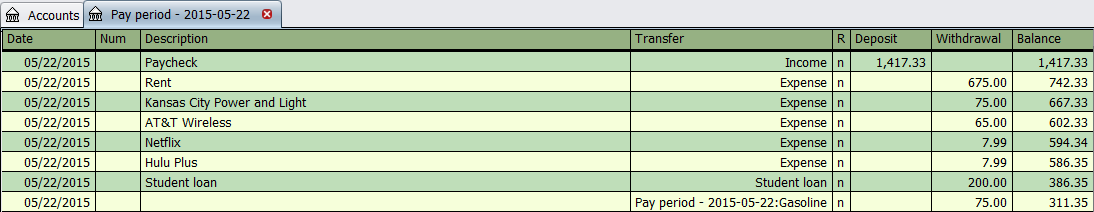

Within the next several business days, the remaining pending transactions will be initiated with the bank, and so I’ll change them to target the appropriate account. Note how the student loan payment targets a Loan account. This is because I follow the standard accounting guidelines for accounting for outstanding loans — i.e. loan payments are not an “expense”.

Looking at the Accounts page:

Now the bank account balance has dropped a bit more. This is because now the expenses are targeting the Expense account. If I were to log into this bank account online, the reported balance should match. But the entire time the “discretionary” never changed — though it would have if additional expenses were added. So as long as spending stayed within that $311.35, you would be fine and would not be at risk of overdrawing your bank account.

Now during the course of the pay period there will be other expenses, of course. Each expense deducts from the “discretionary” balance, so it is important to list all known anticipated transactions up front as shown above so you will know how much you will have available to spend as you saw fit.

Sealing the envelope

At the end of the pay period, zero out the pay period account in a way similar to how you’d zero out the income and expense accounts. You can still do this if you have transactions targeting the “Pending expenses” envelope as the totals would be unaffected.

In all of the sub-accounts for allocations — in our case, just the gasoline account — zero-out the account to the pay period account. If the final balance of the pay period account is still in the black, congratulations, you’ve ended up with a surplus. If it is in the red, this means you spent more than your paycheck and have a deficit. Obviously you want to avoid deficits as much as possible and have as many surpluses as possible, and have those surpluses be as large as possible.

Now zero out the pay period account to the “Checking account” account such that the balance of that account reflects how much surplus cash you have just sitting in the bank not really going anywhere or doing anything. Pay period deficits deduct from this balance while pay period surpluses add to it, and you’ll want to add to it as much as possible and avoid deducting from it where you can.

Obviously there will be times where you’ll need to “tap into” your surplus cash. Things will come up, and my wife and I have had to tap into our surplus before. But it shouldn’t be a habit, and you shouldn’t make excuses to do it either. That surplus is your personal profit, and you want to maximize it by keeping your expenses lower than your income. You can generate a Cash Flow report (Reports->Income & Expense->Cash Flow) to see how well you are managing this. The Liabilities Over Time graph report (Reports->Assets & Liabilities->Liability Barchart) will show the progression of your liabilities for whatever range you specify. You’ll want to keep that on a downward trend as much as possible.

Note as well that you will still want to zero out the Income and Expense accounts to Income Summary, then zero out Income Summary to Net Worth (also called Retained Earnings). Do this at the end of every pay period as well, as this is part of standard accounting practice.

Savings envelopes

Along with having the envelopes for your pay periods, you may also want to have envelopes for certain savings targets. I’ll use myself as an example. I have an espresso maker. It’s a decent one but I have my heart set on a better one.

To set aside that money, I have another envelope account under the “Checking account” account called “Espresso machine fund”. Periodically I will add money to it. It’s still under the “Checking account” account, so the total balance showed on the Accounts page reflects that money, but any money I add to it counts against the discretionary for a pay period, but does not count for or against any surplus cash I have in the bank.

The purchase will come out of that fund account — I won’t move the money to a pay period account before accounting for an expense.

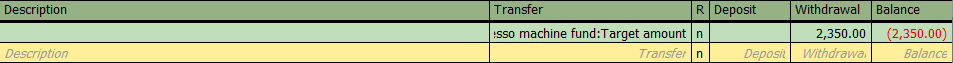

Here’s a little trick.

If you have a particular saving goal, create a sub-account for the fund and call it “Target amount”. If you’re saving for specific expenses, call it “Anticipated expenses”. Now create a transaction entry to transfer the target amount to the sub-account. If you’re saving up for specific expenses, then you’d create an entry for each expense you anticipate — hence the “Anticipated expenses” account.

Doing this doesn’t affect the balance of the “Checking account” account. But it will show you how much more you need to save to meet your goal by putting the balance in the red. If the account ends up over-funded, or you take advantage of a deal that allows you to spend less than you anticipated, the remainder would be moved to the cash surplus, the current pay period account, or another saving fund.

Making it work

There aren’t really any hard and fast rules for this system beyond what double-entry accounting requires — and what GnuCash directly enforces. And that, I feel, is the one advantage to what I was able to develop over time: I didn’t follow anyone else’s rules. I don’t adhere to zero-sum budgeting (or zero-based budgeting, if that’s what you call it) and the rather strict rules that come with it.

For me the above is a system that evolved over time, not something I just adopted out of the blue. I didn’t just wake up one day and say “I’m going to do this”. I started with something smaller and worked into what I currently have. It’s one of the reasons it has worked well for me. I could see quite plainly what changes worked and what did not, what changes added value and what did not.

Splitting things out into anticipated and pending expenses was more about having an immediate check on everything. Does the balance calculated in GnuCash match the balance reported by the bank? And I’m checking that balance several times per day as well to keep things up to date. If there are any transactions that don’t look familiar, I’m forced to look into it (and possibly interrogate my wife) to get things back into balance.

I’m also doing the same with the credit cards, since I do have transactions that auto-bill to them. I want to make sure the balances and transactions in GnuCash match what is listed by the bank and credit card companies. And staying on top of your bank account balance is the best way to avoid overdrafts and get ahead.

Conclusions and Takeaways

If you want to get ahead financially, you need to be spending less than your income. And the best way to make it so your spending can be less than your income is to plan out your expenses versus your income using paycheck budgeting. If you’re not doing that, you leave yourself open to having to borrow or put expenses on credit cards to keep from overdrawing your checking account and paying late fees.

This doesn’t mean you avoid debt entirely, as leveraging credit — such as deferred interest deals — can also help you get into a better financial position, provided you plan for it properly.

I’ve been using paycheck budgeting for the last six years, but I wasn’t budgeting in the full sense of the word, but merely using a spreadsheet to organize obligations against pay periods. Even doing that allowed me to predict months in advance when I would be able to pay off debt accounts and plan to make those pay-offs — a great feeling, to say the least, when you’re climbing out of a massive chasm of debt created by a lengthy unemployment. Loans were paid off in advance, credit card and collections accounts zeroed out.

We were gaining ground, even despite additional liabilities coming onto us in the interim — my wife’s inpatient surgery followed by several outpatient surgeries, parts replacements on the car, and so on.

We got to a point where we were able to buy a used SUV from my mother-in-law for cash split into several payments, while also helping a friend pay off a several-hundred dollar balance on a veterinary bill. Now it helps that we have the income we enjoy, and most households may not be able to get to that point, but you should get to a point where you are making gains instead of feeling like you’re just treading water.

Most importantly, though, keeping those gains requires maintaining the kind of self control that otherwise allows you to make those gains to begin with. It only takes one day, one lapse in self control, to undo any gains you make. Trust me when I say that seeing the cushion of cash (“surplus”) we have just sitting in the bank is quite tempting — I can think of a number of things I could do with that, and so can my wife.

I’ve been using the above-described system for over two years, and I still have a spreadsheet for keeping obligations organized. Along with allowing us to create and meet saving goals, we’ve managed to create a decent surplus as well — though not as large as I’d like it to be, but we’re getting there. But we are ahead financially and gaining more ground each pay period.

More importantly, we stopped lying to ourselves. The financial system showed us the full scope of our situation.

References

You must be logged in to post a comment.