My philosophy on comments is pretty simple.

They’re for explaining outlier situations, not handholding. You don’t write comments to point out the obvious — e.g., “Open the file and parse it as JSON…” And if you are, STOP!

Sure there’s badly written code out there. But in general anymore, if you’re reading through code and believe you need comments to understand what’s going on, you don’t understand 1. the language, 2. the framework (React, .NET, MFC, etc.), or 3. the application and concepts involved. Comments shouldn’t be written so just anyone can jump into the codebase.

And if you’re writing a large comment to explain a block of code, you very likely need to rewrite the block of code. Functionality should be obvious from looking at it. And exceptions to that should be extremely rare.

Instead the aim should be writing code that is self-documenting. We’re long past the limitations of the… past that made meaningful abstraction impossible. All names should be descriptive. And given the comprehensive functionality in most any IDE today, there really isn’t any excuse to NOT make these names descriptive. Again, we’re long past the memory and storage limitations that made meaningful abstraction impossible.

I’ll give an example from my recent experience. As of this writing, I’m finishing up an enhancement for the Ghost CMS stemming from a theme I’m writing. The code base is JavaScript. Themes are a combination of HTML, CSS, JavaScript, and Handlebars.js. I don’t have much experience with JavaScript, and the file I’m modifying has zero comments beyond the comment block at the top, except for one line explaining why an index variable needs to be decremented by 1 – because the why isn’t obvious.

Yet.. I didn’t need comments on every code block or, worse, line of code to understand what’s going on. It was fairly easy to figure out. Comments would likely have just been more… stating the obvious.

DF64 Gen 2 coffee grinder

About a year ago, I wrote about the Timemore Chestnut C3 manual grinder and explained that, while it’s a capable grinder, I bought it merely as a stopgap between the Compak K3 I previously used – and still have, actually – and whatever grinder I went for to replace it.

And the replacement, which I’ve had for about a year as of this writing, is the DF64 Gen 2 (or v2). It’s sold under a couple names, but I bought mine directly from Turin Grinders.

And, sure, there are plenty of videos on YouTube about this grinder, but most of them are made after using the grinder for only a short bit. As I just said, I’ve had it for a year, dutifully grinding coffee about twice a day, typically. Who on YouTube can say that?

So let’s get into this grinder and what you can expect. Starting with the things about it that I don’t like so you can decide if they’re dealbreakers for you.

Very short power cable

It’s 3ft. Seriously?

In a way this worked out slightly for the better, honestly, as my extension cable has a right-angle plug instead of a straight plug. But that I needed it at all is more than a little annoying. It’s added expense on my part that could’ve been avoided with slightly higher manufacturing expense on their part. I mean, how much more would it have cost them to double the power cable length? Can’t be much.

The power cable on the Compak is about 6ft, and that seems to be the standard power cable length for small appliances in the United States when there isn’t a heating element involved. And, again, the DF64’s power cable is only about 3ft.

So depending on your setup, plan to buy an extension cable.

And, a little bit of a PSA, even though this is low-wattage, don’t cheap out on that extension cable. In the United States, you will need a 3-prong extension cable for this – which it’s good to see they do ground it. An appliance extension cable rated for 15A will be ideal here since they’re heavy duty being made for, well, appliances. Sure, overkill given the grinder will only pull a couple amps from the wall after the initial current surge that’s characteristic of most motors. But, again, don’t cheap out.

Power button

It’s a 16mm anti-vandal latching push button, with the plunger sitting about 1/8″ above the button’s collar.

To me, at least, that small button is a little annoying. So if there’s anything I’m going to replace on this, it’ll definitely be that, either with a larger power button or, likely, a toggle switch like on the Niche. I would also very much have preferred that button not be close to the base. But since it’s a push-button power switch, having it low does mean you’re not risking pushing over your grinder every time you turn it on or off.

“Declumper”

Now for easily my biggest gripe about this machine: the acetate “declumper” right before the chute and anti-static prongs.

I’ll just say up front that I completely removed that from the machine after twice having to take apart the chute to clean out grinds that were binding up. And removing that actually improved the results in the cup. I already use the WDT (Weiss Distribution Technique) as I explained in this post, so having a “declumper” that barely functions and over time only serves to create clumps rather than prevent them was far more of an annoyance than anything else.

So if you buy this, the first change I recommend you make is removing that “declumper” – you’ll need to remove the chute to get to it – and just running without it. Just make sure to use the WDT to declump and distribute the grounds in your portafilter.

And on any grinders I buy in the future, removing any “declumper” on the chute will likely be the first thing I do since, again, they tend to make clumping worse as time goes on. The Compak has one that isn’t easily removable, but it also never created a clumping issue that I recall and I used that grinder near daily for over 8-1/2 years.

Dosing cup

My annoyance here isn’t with the cup itself. I actually quite like having it, honestly, as opposed to dosing directly into the portafilter. My annoyance is more around needing the dosing collar that comes with it – that I think can double as a dosing funnel for the portafilter. Because the grinder chute is angled, but the prongs for holding the dosing cup are not. Forget to use the dosing collar and you’ll have a mess.

But at least with mine, the dosing collar is a bit tight around the cup, with the gasket on it not helping, so it never seated down completely. Meaning if you didn’t remove the collar before pouring the grinds into your portafilter, some would get caught along the seam between the collar and cup.

Now it does look like Turin (or whoever actually makes the grinder) has realized this is a problem and no longer includes the dosing collar. Instead they include an adapter that tilts the dosing cup toward the chute. I only learned about this as I’m writing this review, so I can’t speak to how well that works. But I have ordered one as of this writing since it’s only $10.

My only gripe with the dosing cup itself is being aluminum. Even though there is the “plasma generator” for preventing static buildup, it isn’t 100% and never can be, so there is still going be some static causing grinds to stick to the cup. But it cleans out easy enough with just a paper towel. And at least it isn’t plastic.

Small footprint and stature

Okay now let’s transition into what I love about this grinder starting with… it’s small but still uses 64mm burrs – hence the 64 in the name. The K3, by comparison, uses 58mm burrs. It’s the smallest grinder I’ve personally ever owned at only about 12″ tall with a countertop footprint of about 10″x6″. So it should easily fit on any countertop.

Just, again, make note of the short power cable I pointed out above.

Stepless, but easy to adjust

The Compak K3 is also a stepless grinder, but… man the threads were tight making even the slightest adjustments a pain. Tiny adjustments on the DF64 are far easier in comparison. And, again, those threads completely binding up is why I don’t use the K3 anymore.

Minimalist design

The simple design is why I went for the Compak K3 when I bought it back in 2015. Though the DF64 is simpler still since the K3 has a timer so you can dose based on griding time if you want. But the K3 was also from a time when single-dose grinding had yet to become a focus for grinders. The K3 is very much built for commercial use.

The Niche changed that direction, being one of the first single-dose countertop grinders on the market. Prior to that, single-dose grinders were typically manual – like the aforementioned Timemore C3.

And the DF64 is a great competitor to the Niche. The small footprint and that it’s intended use as a single-dose grinder – weigh out one dose and grind that – as opposed to keeping a hopper of beans like the K3 and Breville Smart Grinder I had before that – the one laden with electronics that I replaced with a higher-quality grinder that’s little more than a motor and a power switch…

But the minimalist design also adopted by the DF64 also means it’s…

Inexpensive but not cheap

400 USD. Do I really need to say anything more? Though given the smaller still and lesser expensive DF54 at a little north of half the DF64’s price, I do wonder if the price could come down more for the DF64 Gen 2.

Overall

The price point and positive reviews online for the first-gen DF64 is what prompted me to get in line for the DF64 Gen 2 when those were announced. So my unit was part of the first batch of orders – the ones that have the highest risk of issue. (It’s why I almost never buy games right when they come out. Anyway…) But overall my experience with the DF64 Gen 2 has been overall very positive.

Aside from what I’ve said above about the “declumper” that only serves to create clumps rather than prevent them, along with the need for the collar on the dosing cup, I really have no complaints. Is it better than the K3? Not really, but the only thing separating the K3 from the DF64 Gen 2 is the K3’s more powerful motor, while the DF64 has larger burrs.

Grinders have definitely come a long way since I first got into espresso back in 2012. The question that will be answered as time goes on is longevity. Thankfully it looks like the DF64 is reasonably easy to service, with the burrs also easily accessible. So the question really is going to come down to the motor and how long it’ll be till that gives up the ghost.

Otherwise if you’re looking for a great quality grinder that works well with even the highest-end espresso machines but won’t equally break the bank for you, you definitely can’t go wrong with the DF64 Gen 2.

Buy it now through Amazon, Turin Grinders, or MiiCoffee.

Pardons aren’t without consequences

The President’s pardon power is unconditional and unquestionable. He has the power to pardon anyone for crimes against the United States. And in some last-hour maneuvers, President Biden issued a blanket pardon for Dr Fauci going all the way back to January 1, 2014.

Reason Free Media explains why that’s significant:

But a pardon isn’t all that people make it out to be.

Sure the blanket pardon means that Fauci cannot be prosecuted by the Department of Justice for any potential Federal crimes between January 1, 2014, and January 19, 2025. But there’s more.

First, it doesn’t eliminate the possibility he could be prosecuted for any violations of State laws. It doesn’t eliminate the risk he could be held personally liable for any torts that could be alleged, whether he is sued by any State, the Federal government, or any private party.

But what it does eliminate is the risk of jeopardy.

The Fifth Amendment to the Constitution says:

No person… shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself…

This means that Anthony Fauci, in not timely and publicly rejecting the full and unconditional pardon, can be compelled to testify to anything and everything regarding COVID-19 and the likelihood it was a “lab leak”, along with any gain-of-function research that may have been going on behind the scenes. And the Fifth Amendment is no shield since Fauci no longer has the risk of prosecution.

So in short, if Senator Rand Paul so desires – and he’s probably already being or has been advised of what the pardon actually allows him – he could make Fauci’s life a living hell. And at the first hearing with Fauci as a witness, if I was Senator Paul, after Fauci was sworn in, the first thing I’d be saying to Fauci is, simply:

Dr Fauci, on January 19, 2025, you were pardoned by then-President Biden for all offenses against the United States extending back to January 1, 2014. While that means can you not be prosecuted for any actions, alleged or actual, from then to the date of the pardon, it also means you no longer have the protection of the Fifth Amendment against self-incrimination and can be compelled, under pain of contempt of Congress, to testify to anything and everything related to, quoting the pardon itself, your service “as Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, as a member of the White House Coronavirus Task Force or the White House COVID-19 Response Team, or as Chief Medical Advisor to the President.”

Fauci could not then use that as an opportunity to reject the pardon long after the fact merely because it would be convenient. And if he were to try, the Court would likely say that the time to reject the pardon was when it was delivered to him, not when the full consequences of the pardon became apparent.

But where does it come from the idea the Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination are eliminated when a person accepts a pardon? The same Supreme Court decision that also says a person can reject a pardon: Burdick v. United States, 236 US 79 (1915).

In that case, George Burdick, an editor for the New York Tribune, was subpoenaed to appear before a grand jury to testify to the source of information he had regarding smuggling jewels into the United States. Burdick invoked the Fifth Amendment. And then-President Woodrow Wilson recognized that a pardon would eliminate the risk of prosecution, thereby also eliminating the protection of the Fifth Amendment, and so issued a pre-emptive pardon.

Burdick, however, rejected the pardon and refused to testify, citing the Fifth. He was held in contempt. And the Supreme Court ruled on points that are applicable here:

- Acceptance, as well as delivery, of a pardon is essential to its validity;

- a person can reject a pardon, and the Court cannot then force it on the person;

- the President of the United States may exercise the pardoning power before conviction; and

- a witness retains their Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination in rejecting the pardon.

The Supreme Court had previously ruled in United States v. Wilson, 7 Peters, 150 (1833), that a person may reject a conditional pardon. And Burdick merely extended that to unconditional pardons. Burdick also pointed out that accepting a pardon implies a confession of guilt.

But in stating that Burdick retained his Fifth Amendment protections in rejecting the pardon, it implies that accepting the pardon vacates the Fifth Amendment protections against self-incrimination within the scope of the pardon.

A pardon is merely a ticket to getting out of jail or avoiding prosecution entirely. But it has been long recognized that a pardon, in eliminating the risk of prosecution, also eliminates the protection of the Fifth Amendment against self-incrimination within the scope of that pardon.

What everyone gets wrong about health insurance

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve likely encountered the story of Brian Thompson, the murdered CEO of UnitedHealthcare (herein, “UHC”), one of the major health insurance providers in the United States. And social media being flooded with everyone treating his death like the American version of Red October is about to begin.

One of the stories that came up in the aftermath was UHC’s use of AI, and the broader use of AI in the health insurance industry, and the continual mention that it’s only purpose is to deny claims. And that health insurance companies routinely deny claims in bid to save money because… stockholders.

Except all the discussion on this misses a lot of detail.

Loss ratio

And the first major detail being missed is the regulations that health insurance is subject to. It’s… a lot.

Let’s flash back to 2020 and the pandemic. If you drive a vehicle, hopefully you’re insured. And during the pandemic lockdowns, you more-than-likely got a message from your insurer that you’re getting either a refund or a credit toward future premiums on your auto insurance. Why did this happen?

It’s due to a regulation known as the “loss ratio”. That is the percentage of revenue – i.e., premiums – that must be spent on claims. Every type of insurance has this regulation to ensure they aren’t raking in tons of money on premiums and doing nothing with it.

And, again, every type of insurance is subject to a “loss ratio”. For health insurance, the Federal minimum standard is 80% for individual and small group insurance, 85% for large group insurance. (42 CFR §438.8) So that means every health insurance provider must spend around 85% of premiums on claims. That leaves about 15% for all other expenses. So that means for every $100 in premiums, they must put about $85 to paying claims, leaving the rest for other business expenses and building a reserve.

Which means…

Insurance companies aren’t denying claims purely to save money

Well, they kind of are, but not for the reasons people want to think.

During the discussion on UHC, it was pointed out that UHC had the highest claim denial rate in the industry. Which… okay… that has the potential to be a very misleading statement since… obviously there’s always going to be one who does. So how far away from everyone else are they on that claim denial rate?

Well, turns out, they’re allegedly denying about 1 in 3 claims. That’s… a lot. But that’s not the full story.

First, how many of those claims get appealed successfully? The typical cause of a claim denial is bad paperwork. And generally if there’s an issue with the claim, it should be getting kicked back to the provider who filed it without you hearing about it. But this, I know, doesn’t always happen and an insurance company may still send out an EOB on a problem claim showing the claim was denied.

And if you receive such, your next move should be to talk to whomever filed the claim so they can handle any issues and resubmit. Because.. mistakes happen.

There’s another possibility to entertain as well. Remember that “loss ratio” I mentioned earlier? If UHC’s claim denial is legitimately that high, meaning they are denying 1 in 3 claims, none of those denials are overturned on appeal if they’re appealed at all, UHC is complying with the loss ratio regulations, and you remember anything from your high school math courses, something else should be obvious: UHC is denying low-cost claims to pay out the high cost claims.

“High cost claims” would include things like… surgeries or lengthy hospital stays. “Low cost claims” would be things like doctor visits and prescriptions.

So, again, if UHC was legitimately denying 1 in 3 claims but still being compliant with the loss ratio… that’s the only explanation. They’re prioritizing the fewer big claims over the far more numerous smaller ones.

Which UnitedHealth Group’s balance sheet reports an overall loss ratio of about 83.2% for 2023.

Insurance companies aren’t as profitable as many think…

I’ve discussed business profit before on this blog. In short a lot of people have a lot of wrong ideas about it, starting with presuming the “profit” reported in the news and on financial statements is cash in the bank. And that presumption was on display in the wake of the UHC CEO’s death:

UnitedHealth Group’s cash flow statement paints a far different picture. Their cash position, the actual cash in the bank, increased by only $2 billion in 2023 across UnitedHealthcare and Optum, both of which are UnitedHealth Group subsidiaries. (As of this writing, final figures for 2024 are not yet available.)

Their change in cash position compared to almost $368 billion in revenue also means not even a 1% cash profit margin.

And, here’s the kicker, that’s funded by a $4 billion increase in long-term borrowing, with their balance sheet showing them sitting on over $62 billion in long-term debt. Without that increase in long-term borrowing, they would’ve had a cash shortfall of about $2 billion.

… and they can run out of money

This is a reality of insurance a lot of people don’t want to consider and goes beyond the loss ratio.

An insurance company isn’t going to pay out only up to the loss ratio and nothing beyond that. That’s how they get sued. But insurance companies aren’t sitting on bottomless buckets of cash either. And claims may get denied by an insurance company for the simple fact… they can’t pay on it. So they may kick back a claim merely to delay it.

Back in 2011, Cracked.com posted an article called “5 Useful Organizations You Think Are Evil (Thanks to Movies)“. Unsurprisingly on that list is insurance companies.

But you can’t lose sight of this: The thing that we really want insurance companies to do — pay for everything every deserving sick person needs, ever — is physically impossible.

Transport yourself to an alternate dimension where every insurance company employee is 100 percent honest and 100 percent compassionate. We’re talking a company whose cubicles and board of directors are both full of Mother Theresa. By the sheer, mathematical realities of the insurance industry, they will still find themselves denying claims to poor people who badly need care.

This is why during that health care debate, the opposing sides were both able to cite coverage-denial horror stories from every single system on Earth. Horror stories will always be part of the equation. It’s as simple as this: We want insurance companies to say money is no object when providing coverage, but we don’t say the same when paying premiums. That creates a gap into which sick people fall and die.

Again, though, a lot of people seem to presume that insurance companies – and businesses in general, if you look at the minimum wage debates – are sitting on bottomless buckets of cash. And the thought that insurance companies can run out of money just never occurs to people. No, if a claim is denied, it’s entirely because greedy corporate billionaires want grandma to die because it’s better for their bottom line.. Give me a fucking break…

Your premiums cover claims plus all other business expenses – this includes things like taxes and salaries. And under Federal and State labor laws, everyone who works for the insurance company must be paid their agreed upon compensation. So if an insurance company can’t make payroll and pay the claim for your mother’s open-heart surgery, guess which one takes priority…

And…

Making all health insurance non-profit won’t change that

In the general sense of the term, “profit” means only that a company did not overspend their revenue, meaning even non-profit organizations also need to… turn a profit. Meaning, like all other businesses, they can’t overspend.

And we have non-profit health insurance in the United States.

The Blue Cross Blue Shield Association is a 501(c)(4) public welfare non-profit organization, as are all member organizations. Not the only one, but easily the best known name. Does anyone honestly think they never deny claims merely for being non-profit? While non-profits that run in the red can turn to donors to make up the shortfall, a non-profit organization that is careless with its cash will soon lose their donors.

Single payer isn’t unlimited either

The idea that insurance companies can’t run out of money is topped only by the idea that the government can’t either. Proponents of single payer health insurance in the United States seem to think that, under such a system, no one will be denied care, everyone’s claims will be paid, nobody will die of anything, and… everything will be just great!

Reality, though, paints a far more bleak picture. For starters, look no further than the Department of Veteran’s Affairs, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and health care on the various Native American reservations.

It also highlights that few in the United States remember the COVID lockdowns and why those occurred. Namely to prevent the entire health care system from being overwhelmed, insurance included. Since hospitals do not have an unlimited number of beds, clinics don’t have an unlimited number of exam rooms and personnel, pharmacies don’t have an unlimited supply of drugs, and insurance doesn’t have an unlimited amount of money.

Yet advocates for single payer seem to presume that, under a single payer universal healthcare system, all of those limitations just magically vanish. Yet most every country in the world was having COVID lockdowns, including the ones with single payer universal healthcare! The reality of what would happen under single payer is highlighted with what happened after the Affordable Care Act started taking effect: demand for health care would surge.

And with single payer, wherein all cost of healthcare gets foisted onto the government, it could easily overwhelm supply because the cost incentive to dissuade consumption and engage in preventative measures is not there.

The reality of single payer, as well, is it can only work when demand for health care doesn’t even meet supply, let alone exceed it. The same applies to insurance overall, actually, not just health insurance. Meaning with health insurance, you need a generally healthy population. A lot of European countries fit that specification. The United States… absolutely does not. And a lot of the countries everyone points to also have a lot more providers per capita than the United States, a metric known as “physician density”, something else I’ve also discussed on this blog.

And speaking of “countries everyone points to”, it also hasn’t escaped my notice, at least, that when discussing single payer, everyone points to countries that are an order of magnitude smaller than the United States as models the US can follow. I’ve already debunked that notion, so I won’t address it again here. They never point to health care in countries like… China and India, Pakistan, Brazil, or Indonesia. Countries much closer to the US in population – or bigger in the case of China and India – than the largest of the European countries.

Again, it’s extremely regulated

The notion that the United States has “unfettered” capitalism gets thrown around so much. And with that comes the thought that, since the United States has “unfettered” capitalism, nothing is regulated. Not health care and insurance, finance, drugs, food, automobiles. Nope, nothing. It’s all unregulated and companies can do whatever the fuck they want.

And that’s not even close to reality.

But even when the notion that nothing is regulated is not being proffered, a similar mindset is still on display. That an industry, as opposed to the entire economy, isn’t regulated at all if the industry or specific players within it do anything they don’t like. Insurance company denies claims? Industry needs a governing board and regulation. Despite being one of the most heavily regulated industries in the country.

And a similar idea was floated back during the health care debates ahead of the ACA passage, and in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. Finance and health care are the most regulated industries in the United States, and were even prior to 2008. And contrary to popular belief, neither were ever “deregulated”. Instead the details of those regulations changed. It was labeled a “deregulation” because some regulations were repealed, but only so those could be replaced by others.

And a lot of people have the thought in their minds that repealing regulation, regardless of the reason, is always “deregulation” and always bad.

Insurance companies aren’t “practicing medicine”

No, seriously, they’re not.

In all the discussions about health insurance, the idea that insurance companies are denying care crops up all the time. And from this comes the idea that insurance companies are practicing medicine.

I’ve also seen the notion that the percentage of claims denied by insurance should always be zero, that insurance should pay on every submitted claim regardless of the details and whether the claim is just pure fiction. And that insurance companies should never be second guessing physicians, that if a physician says a patient needs something, insurance should pay for it regardless of the details or whether the idea is just completely laughable or entirely fictitious.

Setting aside how pervasive that would allow fraud to become, it flies in the face of the basic reality that health insurance is not sitting on bottomless buckets of cash. Even if UnitedHealthcare was operating on a 100% or higher loss ratio – given the amount of cash and equivalents they’re sitting on, according to their balance sheet – that still means they will eventually have to deny claims.

But when a claim is denied, insurance isn’t denying care. Only payment. The question then becomes how the provider and patient settle what the provider is alleging is owed.

But in most instances, insurance is brought in after the fact. I’ll use my most recent ER visit as an example since… there was no preapproval for setting my shoulder after I dislocated it. There also wasn’t any kind of preapproval for physical therapy, only periodic measurements for continued approval from insurance. Meaning eventually Cigna would choose to not continue paying their end of it.

And I think that came after about 16 sessions, twice a week.

Cigna didn’t say I could not continue the physical therapy, only that they weren’t going to pay anything toward it. Meaning if I did continue, it was entirely my cost. And I did keep going after that for a couple more weeks, following on my PT’s advice.

Sure one could say that insurance should’ve kept paying so long as I kept going. But that insurance decided to cut me off raised the question with the physical therapist of whether I still needed directed physical therapy. And Cigna chose to cut me off because my latest round of measurements showed my range of motion was pretty well back to normal.

Again, though, we did continue for a couple more weeks to make sure there weren’t any underlying issues that had yet to present. That then freed up the physical therapist’s calendar for patients who needed the directed therapy a lot more than me.

And insurance deciding to cut me off also freed up that little bit of money they otherwise would’ve spent on me to instead be spent on another patient.

You can’t “vote with your wallet”

In a market economy, that potential customers can “vote with their wallet” by walking away to competition is generally what keeps businesses doing what they can to keep customers happy. It is the check people have on market players, and it’s extremely important. If one brand has been going downhill in quality, excluding one-off issues that can never be completely eliminated, you generally have other options if reaching out to the brand doesn’t result in a change of course. And social media today gives you a platform to voice your dissatisfaction with the reasons for your dissatisfaction.

And where those checks cannot properly function or otherwise fail, the law provides a fallback wherein people can raise grievances to seek redress and compensation for any losses or damages.

That option largely doesn’t exist with health insurance in the United States. And a lot of that is thanks to the Federal government.

In an actual market economy, UnitedHealthcare would never be able to get away with a reported 1 in 3 denial rate on claims. Their customers would walk unless there was a very, very good explanation from UnitedHealthcare as to why their denial rate was that high.

But… customers largely… can’t just walk away.

If UnitedHealthcare is the employer-sponsored health insurance, employees can’t drop that until the company’s open enrollment period. And the employer also can’t drop it until their renewal period comes around – provided they aren’t locked into a multi-year contract in exchange for lower premiums.

And if the insured has a private plan through UnitedHealthcare, again, they cannot walk away from them until open enrollment unless you have a qualifying life event.

And you can thank the 111th Congress for this state of affairs with the inaptly-named Affordable Care Act.

That eliminated choice in the health insurance market in the United States by reducing everything down to just four options – bronze, silver, gold, and platinum – if you weren’t getting insurance through your employer. Throw on top the “individual mandate” and requirements for what even individual plans had to cover – e.g., maternity even if the policy holder is male or a woman unable to get pregnant – along with the fact it was sold to Americans with wild promises that never came to fruition.

The requirement that, for example, single men purchase insurance with maternity care stems from the false idea that insurance companies were maintaining separate pools for each type of coverage when there’s nothing to suggest any health insurance company was doing anything of the sort. Instead you purchased care you needed, and insurance companies paid out claims pursuant to the loss ratio.

Before the Affordable Care Act was passed, I was able to buy an individual health insurance policy without having to wait for a specific enrollment period. And the plans were relatively inexpensive since you weren’t forced to buy coverage you were never going to use.

Now that option is not available unless you have a qualifying life event. And the premiums skyrocketed as well, nearly tripling in the about 6 years I had the plan before I canceled it as a new employer had a better employer-sponsored plan through the same company – Blue Cross Blue Shield of Kansas City – for less out of my paycheck compared to what I was paying per month on the individual plan.

And single payer eliminates choice entirely. Since if the single payer provider reveals that they were denying 1 in 3 claims, you can’t go anywhere else. You’d have no choice but to just… live with it.

Which, unfortunately, isn’t much different from the current state of affairs.

Installing Volumio into VirtualBox

Three simple steps:

- Download the Volumio image

- Convert the Volumio image to a VHD

- Create the VirtualBox VM using the converted VHD

Note: Follow these steps on your VirtualBox host.

Download the Volumio image

Go to their download page and download the PC (X86/X64) option. Extract the .img file from it using your favorite compressed archive utility.

Convert the Volumio image to a VHD

Now to convert this to something that VirtualBox can use. And VirtualBox provides a command-line tool to do this: VBoxManage. So run this command:

VBoxManage convertfromraw \

/path/to/downloaded_volumio.img \

/path/to/converted_volumio.vhd \

--format=VHDOn Windows, VirtualBox does not install itself into the path, so you’ll need to do this first:

path=%path%;C:\Program Files\Oracle\VirtualBoxOnce you have the converted Volumio VHD file, you can create the virtual machine.

Create the VirtualBox VM

Note: these steps presume you’re using VirtualBox 7.1 or later. In the VirtualBox Manager, create a new VM with these settings:

- Name and Operating System:

- Name: Volumio

- Type: Linux

- Subtype: Other

- Version: Other Linux (64-bit)

- Hardware

- Base Memory: 4096 MB

- Processors: 2

- Hard Disk

- Use an Existing Virtual Hard Disk File: (Add the converted Volumio VHD made earlier)

Click Finish. We’re not done yet. Open the settings for the new VM and change these settings:

- Display

- Video Memory: max it out

- Storage

- Remove the IDE adapter and CD drive

- Network

- Adapter 1

- Attached to: Bridged adapter

- Adapter 1

And click OK, then start the VM, preferably using a Detachable Start. It should boot successfully into the UI, presenting you with the first run setup.

Why we “romanticize” past developers

Let’s look at this:

And quoting it directly in case it disappears later:

People like to romanticize the devs of the past. “People just don’t care about engineering now…”

JFC, there was an entire crisis(Y2K) that had to be averted because 70’s and 80’s devs couldn’t think past the year 1999 because they wanted to save a couple bytes.

Software engineering is just as lazy as it’s ever been, we just have more ways of doing it now.

Looking through his profile, he lived through Y2K, going into community college starting in 2009. And he likely also would’ve learned in his programming classes why that happened. Meaning to say the software engineers of old wanted to save 2 bytes, and so got lazy in their coding, is just outright stupidity.

And what we largely have here, what Chris is putting on display, is taking the technology of today, the standards of today, and applying them to past events. He’s taking what is possible today – the fact we can store all 4 digits of the year without issue in any system – and acting like it had to have been possible back then.

And technically it was. But there were significant trade-offs. Because there were significant limitations that Chris has never had to face. Limitations the majority of software developers alive today have never had to face.

Two of which were processing speed and storage capacity.

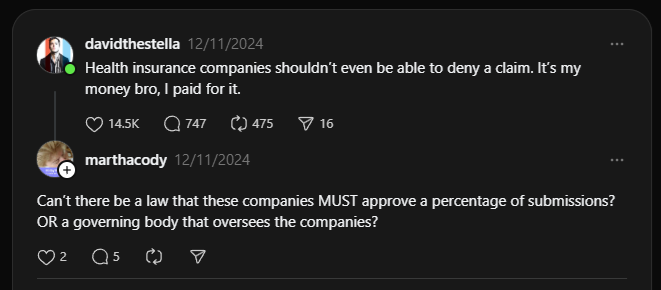

On the latter, you’re probably aware that your cell phone today has more processing power than all of the computers that allowed NASA to put Apollo 11 on the moon. You’ve probably also seen this famous picture of Margaret Hamilton standing next to a printout of the code that she and her team wrote to accomplish that:

And back in the 1960s, the whole field of computing and software development was in its infancy. The code that Hamilton is standing next to is dwarfed by anything today in terms of functionality and size. Because back then computers didn’t have the breathing room for everything we take for granted today, and took for granted even 20 years ago when Windows XP was still the dominant operating system with Vista on the horizon.

Meaning cutting 2 bytes out of a record size made all the difference.

This blog post wouldn’t even fit in RAM on most desktop computers from the 1970s and 1980s. The full-size version of the above picture available on Wikipedia Commons wouldn’t fit in the RAM on the IBM XT I used when I was a kid back in the 1980s.

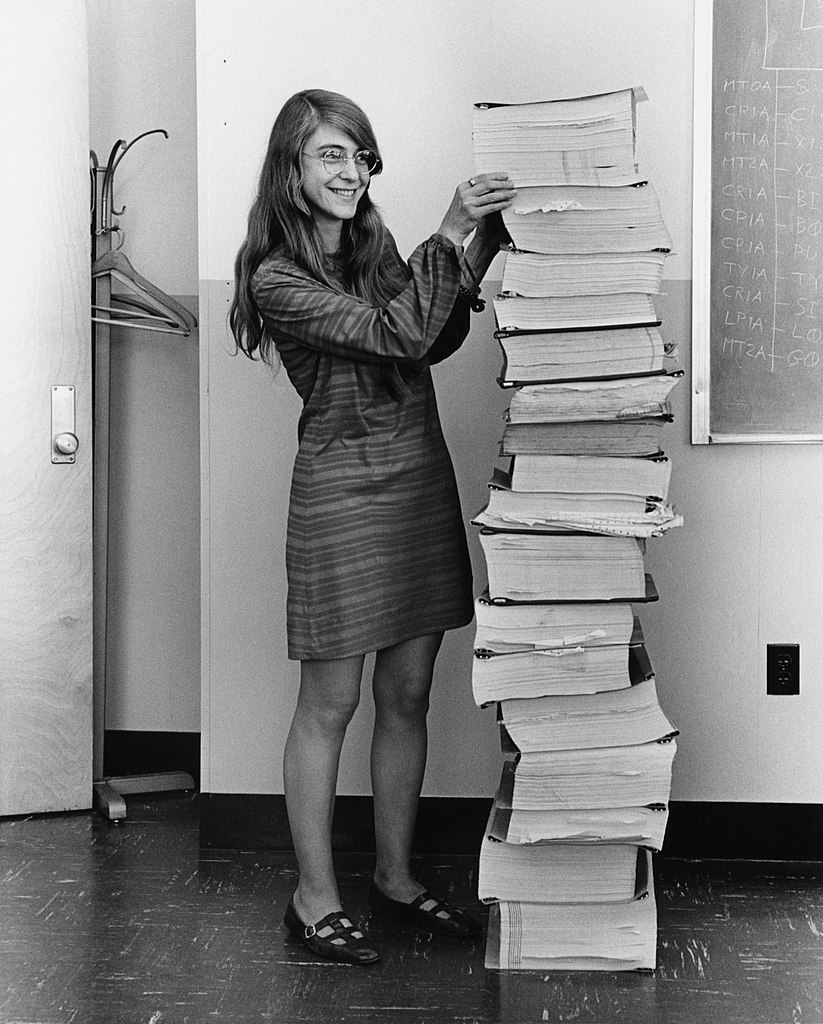

That isn’t to say that people are spoiled today, though they certainly are. Programmers especially. Imagine writing programs for this:

That is the Texas Instruments TI-82 graphics calculator. It was considered a pocket computer back when I was in high school, sporting a Zilog Z80 processor running at 5 MHz with 32 kilobytes of RAM… oh wait, let me repeat that. It had just 32 KILObytes of RAM. Of which 28 kilobytes was user-accessible and the other 4KB reserved for the “operating system”. And that RAM was used for storage as well – if both the AA batteries and the coin cell battery died, you lost everything stored on it. (The OS was stored on a separate ROM and copied back into RAM after the batteries were replaced.)

For comparison, the computer I’m using to write this blog post has 32 GIGAbytes of RAM. A million. times. more.

The preceding TI-81 was worse still, having only 2400 bytes of user-accessible RAM. Imagine writing a program for that! Given Chris’s post above, I think that needs to be part of any modern programming curriculum.

As a calculator, the TI-81 and TI-82 were very capable, but I very much preferred the HP 48 I had in my high school AP calculus class. (Pretty sure it was the 48G.) It had a more capable programming language compared to the TI-BASIC featured on the TI-82, though it’s reverse-polish functionality took some getting used to. The 48G wasn’t much better than the TI-82 in terms of user storage, but it at least gave you the full 32 kilobytes. The GX had 128 kilobytes. It also used a separate 512KB ROM for the “operating system”.

Back when I was first learning to program, the early 1990s, my father gave me a torn up book of text-based games written in BASIC – the Beginner’s All-purpose Symbolic Instruction Code. And it was fun and one hell of a learning experience taking those programs and adapting them into TI-BASIC for my TI-82 and, later, the TI-85.

The largest in that book was a Star Trek game. It wasn’t possible to convert that for the TI-82 due to limits in how many lists and matrixes it could store, but I could just barely convert it for the TI-85. It took forever to type into the calculator and barely fit due to the storage limits. But when I showed it off to my friends at school, it immediately made them envious.

Anyway…

When the total memory space for your code and any variables it uses is measured in only kilobytes, imagine the compromises you have to make, the ingenuity you needed to exercise to write a program that met your requirements – after convincing the bean counters that half what they wanted isn’t even physically possible.

Then scale things down smaller still.

We’re talking about a time when single-character and two-character variable names were the norm out of necessity. Because having longer variable names peppered through your code meant risking running out of storage space for the code, provided your compiler or interpreter didn’t run out of memory trying to process it. Comments weren’t really a thing either, again due to storage and memory limitations – they were almost non-existent in that BASIC programs book I mentioned earlier.

As memory and storage capacities grew, and processors became far more capable, better practices were adopted. More comments for your code started becoming a thing, followed by self-documenting code. Frameworks and APIs became more capable as well because the systems that would be compiling or running the code could handle all of that without running out of memory – mostly.

We romanticize the developers of the past – including those like Margaret Hamilton and her team, Adm. Grace Hopper, Dennis Ritchie, John Kemeny and Thomas Kurtz – because of the limitations they had to work with, because of what they were able to accomplish despite those limitations.

Again, Hamilton and her team wrote the code that helped put Apollo 11 on the moon. And programmed that for systems dwarfed by even my TI-82.

And, again, those are limitations software engineers today will likely never have to face.

Chart.js and Ghost

I’m migrating this site over to Ghost. Over the 15+ years I’ve had this blog on WordPress, there are a few plugins I’ve come to rely on heavily. And the one that’s been the toughest to find an alternative to is Visualizer. It renders the graphs on the several pages that use it, such as my very long article on abortion.

In the search I discovered Chart.js, which looks to be a viable replacement. But integrating it into Ghost isn’t all that easy. Rather than use code injection on the posts where I want to use it, I opted to create a “partial” that is scoped based on an internal tag:

{{#is "page,post"}}

{{#post}}

{{#has tag="#chartjs"}}

<link rel="stylesheet" href='{{asset "css/chartjs.css"}}' />

<script src='{{asset "js/chartjs/chart.js"}}'></script>

<!--<script src="https://cdn.jsdelivr.net/npm/chart.js"></script>-->

<script>

function chart(chart_options) {

new Chart(

document.getElementById(chart_options.container_id),

{

type: chart_options.chart_type,

data: chart_options.chart_data,

options: {

responsive: true,

plugins: {

legend: {

position: chart_options.legend_position || 'right'

},

title: {

display: chart_options.display_chart_title || true,

text: chart_options.chart_title

}

}

}

});

}

</script>

{{/has}}

{{/post}}

{{/is}}

This is the code I’m using as of this writing. I’ll update this post as I go, but for now this appears to give me what I want. I have the above in a partial – chartjs.hbs – and call it from within the header on my default.hbs template file after everything else. That way I’m not relying on per-post code injection to use it. Instead I rely on an internal tag – #chartjs – to turn it on for posts that use it over loading it for every post.

For the time being I’m not loading chart.js externally while I’m developing a theme, hence the CDN line being commented out in favor of pulling from the assets.

And this is an example of calling the chart function through an HTML card to provide a line graph like this:

<div class="chartjs"><canvas id="mass-shootings-per-year" /></div>

<script>

chart({

container_id: 'mass-shootings-per-year',

chart_type: 'line',

chart_data: {

labels: ['1982', '1983', '1984', '1985', '1986', '1987', '1988', '1989', '1990', '1991', '1992', '1993', '1994', '1995', '1996', '1997', '1998', '1999', '2000', '2001', '2002', '2003', '2004', '2005', '2006', '2007', '2008', '2009', '2010', '2011', '2012', '2013', '2014', '2015', '2016', '2017', '2018', '2019' ],

datasets: [{

label: 'Mass shootings',

data: [ 01, 00, 02, 00, 01, 01, 01, 02, 01, 03, 02, 04, 01, 01, 01, 02, 03, 05, 01, 01, 00, 01, 01, 02, 03, 04, 03, 04, 01, 03, 07, 05, 04, 07, 06, 11, 12, 10 ]

}]

},

chart_title: 'Mass shootings per year, United States, 1982-2019'

});

</script>Which looks like this:

This can definitely be enhanced further, and I’ll update this post or put everything on Github as things progress.

Labels won’t save you

Over on Threads, a user going by brandothecommando_ said this:

If you are a photographer don’t put non refundable deposit for booking. If you get sued you may end up having to pay back the client’s deposit. Use non refundable retainer or booking fee. Please keep in mind the verbage you use for the contracts so that way it’s strong. And for the love of god as a photographer make sure you don’t break your own contract and loose out on money because you got sued.

And since I’m writing this article, it should be plainly obvious that this is NOT correct. Before we dive deeper, here was my reply:

Nothing wrong with calling it a deposit. Since “deposit” implies that it will be credited toward the final balance without needing to spell it out.

“Retainer” or “booking fee” have different meanings under common law and it won’t be clear, unless you spell it out in your contract, that said “retainer” or “booking fee” will be credited toward the final balance and isn’t a separate charge.

But you do need to make it clear that the deposit is non-refundable except where required by law.

And calling it a “booking fee” or “retainer” doesn’t save you from having to refund that if you’re sued and the client is seeking a refund of everything paid because you failed to uphold your end of the contract.

“Deposit” vs “retainer” or “fee”

If I say that I charge $1,000 for a photo shoot and there is a $500 deposit due up front, what is your assumption? Likely that the $500 is going to be credited toward the $1,000 (plus any other fees per the contract). But if I call it a “retainer” or “booking fee”, you’ll likely think that fee is a separate charge from the $1,000.

And so will the law.

The easy demonstration on this is the “application fee” for an apartment vs the “security deposit”. The security deposit is credited toward anything you owe your landlord after you move out. This could include costs to clean the apartment to get it ready for the next tenant or repairs to any damage you cause. And if the deposit you paid is more than the costs incurred, the landlord is supposed to refund the remainder – unless the contract says it won’t refund anything less than a certain amount, like anything under $10.

Fees are also typically not refundable, but deposits generally are. Unless you say the deposit isn’t refundable. But to elaborate on that idea, I’ll just pull in the section “Non-refundable deposits” from this article:

If you’ve bought a house, you should be familiar with “earnest money”. For those not in the know, it’s a cash deposit (mine was $500) that shows that you are serious about buying the house. It is credited toward your closing costs, but is non-refundable if you back out of the purchase with some exceptions (e.g. you discover something substantial about the home not on the seller’s disclosure form).

So for services booked months or longer in advance, the non-refundable deposit is similar to “earnest money”. It shows you’re serious about their services, secures them for the date in question, and is non-refundable should you back out.

Making anything similar to this idea incorrect: “Services were never rendered, so the videographer has no right to keep the money.”

And the contract will stipulate the deposit is not refundable under any circumstances (except where law requires), or will give only some circumstances in which the deposit may be refundable in whole or part. This doesn’t mean the money is absolutely gone. But getting it back requires getting the contract nullified in Court (good luck there!) or the other party (photographer, etc.) must have backed out for some reason or failed to show.

That doesn’t mean the service provider cannot refund the deposit under any circumstances. Only that they won’t be obligated to do so under the contract for circumstances not expressed in the contract. The refund will, instead, be entirely at their pleasure.

You’re free to request it, but they won’t be under any obligation to give it.

So this begs the question, when is a non-refundable deposit actually refundable?

Refunding a non-refundable deposit

Obviously the party receiving the non-refundable deposit always has the option of refunding it absent an obligation to do so. So when is there an obligation? In short, when the contract or the law says so. The contract can enumerate conditions under which the deposit is refundable in whole or part, thus creating a contractual obligation – e.g., when the opposing party dies.

But when is there a legal obligation where the contract is otherwise silent? Generally the party receiving the deposit must be in breach of contract. (There are plenty of other circumstances wherein that money, and potentially more, may be recoverable by the other party, but I’m not writing a dissertation here.)

Going on photography, since that’s the context for the statements that prompted this article, that would mean the photographer fails to show for the shoot for reasons not outside their control, or fails to otherwise fulfill their obligations under the contract – e.g., not turning over the photos in the amount of time the contract specifies, absent extenuating circumstances. And if the photographer recognizes they’re in breach, they should do the right thing and refund the deposit without any fuss.

But if they don’t and their client sues them, the client can seek refund of the deposit and remedy of any other damages since the photographer failed to uphold their end of the bargain. And calling it “non-refundable” won’t help you. Saying the deposit is “non-refundable in all circumstances” is unenforceable.

And calling it a “booking fee” or “retainer” won’t save you either.

Since if you’re sued and your client is seeking monetary damages where injunctive relief won’t suffice or isn’t possible, and the Court rules against you, the Court will order you to pay a specific amount based on the losses or damages the client incurred. An amount which will likely also include everything the client paid you – i.e., all deposits, fees, and the like.

“If the service didn’t happen”…

The above-mentioned user replied to me:

Calling it a deposit is meaning you are paying for a service in advance in the future. Even if you call it non refundable and let’s say the service didn’t happen and client were to sue you would lose.

I’ll admit I got a little harsh in my feedback, but at the same time I also have a LOT more than a layman’s understanding of contract law. As I’ve said before, there are a lot of misconceptions floating around about how contracts work and don’t. But their reply to me also highlights that people will say contracts aren’t bulletproof, which implies they’re easy to get out of, while also saying that money is easy to shield from a lawsuit by… labeling it something else.

Yeah that’s not how it works.

It isn’t as simple as “if the service didn’t happen”. It really depends on WHY it didn’t happen.

You really need to learn about contract law before speaking like you know what you’re talking about. Because it’s painfully obvious you don’t given you think calling it a “booking fee” or “retainer” instead of a “non-refundable deposit” somehow shields that from recovery should your client sue you and win a monetary award against you – regardless of why they’re suing you.

And while you’re learning about contract and common law, make sure to also brush up on how relief works in the context of a civil suit outcome. Monetary relief and injunctive relief. Since if your client sues you, everything the client paid you and then some is potentially recoverable.

And there isn’t anything you can write into your contract that will shield anything your client pays you. Not even a “liquidated damages” clause can do that depending on why your client is suing you.

Since depending on WHY your client is suing you, the tort that is alleged and the damages the client is seeking to recover, they could end up recovering MORE than what they paid you. Since the lawsuit is entirely about making the party who is injured as whole as possible.

Which is why business insurance is so, so important.

Sure your client could sue you if the service doesn’t happen. They can also sue you for looking at them funny if they decide to call it “harassment”. Whether they prevail is a different story, and a lot of… caustic people in the world know that merely threatening a lawsuit often is enough to get someone to comply with their demands, however unreasonable.

The point of a civil suit is to make an injured party whole as best as possible. Which is why no language in a lawsuit can shield from recovery anything a client pays you.

While I’ve said before that contracts are damned hard to get nullified, there is one reality about contracts that everyone needs to understand: where the law and a contract conflict, the law wins. Put anything into a contract that conflicts with common law (i.e., Court precedent) or statutory law and the Court will rule it unenforceable.

Put any language in the contract that attempts to shield from recovery via a lawsuit anything your client pays you, the Court will rule that unenforceable if you’re sued and just act like that language was never there in the first place.

Talk about short-sighted

Article: Letters to the Editor: Trump has vowed revenge. Start the pardons, President Biden

From the above:

To the editor: Harry Litman relies on the wisdom of grand juries, juries and judges in protecting the subjects of President-elect Donald Trump’s enemies list. However, even unsuccessful prosecutions could bankrupt many innocent “defendants.” (“Will Trump launch a reign of terror against his list of enemies? There’s little to stop him,” Opinion, Nov. 7)

The easiest way to provide all of “Trump’s perceived enemies” with legal (and financial) protection from frivolous prosecution would be for President Biden to compile an enormous list of people to pardon before he leaves office, including prosecutors, judges, journalists, pollsters and others.

Jack Smith, Liz Cheney, Adam Kinzinger, Adam Schiff, Kamala Harris, additional members and witnesses of the House Jan. 6 Committee and many others come to mind.

This won’t eliminate the threats to democracy, but at least it might provide protection for some people.

Mark Henderson, Folsom, Calif.

Pardons and clemency by the President or a Governor require the person being pardoned to accept it. In accepting a pardon or clemency from the President or Governor, you are also openly admitting guilt to at least what is mentioned in the pardon. Even if you don’t explicitly say you’re guilty, accepting the pardon means you’re saying you did it unless the pardon states clearly that you are being pardoned because you’re innocent.

So, for example, if the Governor of Kansas were to issue me a pardon for, at the extreme, murdering a police officer, accepting that pardon would mean I’m admitting to being a cop killer.

Meaning, given the above, if President Biden were to preemptively pardon all the individuals so named, plus himself and others, those individuals accepting the pardons would, more or less, be an confessing and admitting guilt to at the least whatever is outlined in the pardon. Meaning it absolutely would NOT be in Biden’s interest, or the interest of the Democratic Party, to even consider issuing such pardons. But if Biden were to ignore that and issue them anyway, it would also not be in the best interest of those being pardoned to accept them.

At the same time, the pardons also eliminate any protection of the Fifth Amendment to whatever is named in the pardon, meaning the individuals who are pardoned can be compelled via subpoena from a Court or Congress to provide testimony to whatever is named in the pardon. Since a preemptive pardon is, in effect, a grant of immunity, meaning self-incrimination is impossible.

Meaning the grants of pardons, and their acceptance by those pardoned, won’t end any investigations. It’ll only amplify them.

I don’t think Mr Henderson from Folsom, CA, really thought this through.

Atheism has nothing to do with it

Let’s get into this:

Now I’m not going to start off by saying anything positive about the speaker here. I’m just going to dive right in and say that Gothix is wrong here.

She pulls the same fallacy I see time and time again from the right by conflating a lot of negatives with atheism. Here she starts off by saying that a sense of urgency among leftists, such as the climate alarmism, is due to leftists being atheist and trying to make their own heaven on Earth since they don’t believe in a Heaven after death. Which has a bunch of implications, but I’m not taking that tangent.

So let’s keep this just on Gothix and her statement that most on the left are atheist:

First of all if we look at the breakdown of people who tend to be involved in psychology, these people tend to lean more one way on the political spectrum. Okay they… they usually tend to be left liberals, progressives. Most people on the left tend to be secular, tend to be atheist.

Secular, yes, but not atheist. No, they are not the same.

Nearly 3 in 4 people in the US is Christian according to the World Religion Database as of 2020. Meaning a very substantial portion of those she’s attempting to describe are actually people who DO believe in an afterlife, don’t believe that this life and world is all there is. And the US has gotten more religiously diverse over the years as well courtesy of immigration.

Then there’s the flip side of her statement: that atheists are leftist. And, no, that isn’t the case. There is a very sizeable portion of atheists and agnostics who are conservative and libertarian – something that continues to surprise a lot of atheist talking heads. Sure the majority of atheists are left-leaning, but left-leaning doesn’t mean leftist, and progressive doesn’t mean leftist either.

The number of people who are leftist is actually relatively small. They’re very vocal, yes, but they aren’t even a plurality of everyone who falls left of center.

But there’s also a lot of political diversity among the religious, too. Liberal and leftist Christians, for example – yes, they exist. “Blue Dog Democrats” are another. The guy who penned the original Pledge of Allegiance was a Christian socialist.

So can we please stop acting like everyone who’s left of center is an atheist and everyone who’s right of center is religious? That fallacy has been floating around for so long that I see atheists repeating it. And the number of times I’ve been called a Christian merely for disagreeing with atheists is staggering…

So Gothix is just engaging in more of the same misrepresentation of atheists I’ve seen time and again.

And to summarize, most atheists are left of center, but most of those who are left of center are religious to some degree. Simply because most people are religious to some degree. And a sizable portion of atheists are conservative or libertarian.

You must be logged in to post a comment.